I have just finished another one of Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond Chronicles. Do you read a book by her, or rather, eat it slowly, blindfolded, seeking to identify the ingredients that constitute its rich sauces? Each and every page there is cause to pause, to peel back the deceptive words for the hidden nuances that lie beneath, which reveal the roiling depths of her layered characters.

If Jane Austen did not “… write for such dull elves as have not a great deal of ingenuity themselves”, then Dunnett positively demands only the brightest of the elfin kingdom. I frequently wonder when I am reading her, whether I have the qualifications. Using language that shimmers and entices in a way that only the Celts know how, she categorically refuses to explain herself, except perhaps 200 pages later, when you have finally stumbled into an understanding such that you no longer need it.

Her point-of-view is stratospheric, never delving into the depths of her hero’s convoluted motives from the inside, but hiding them in every phrase for the reader to fossick through as best they can. It is, in my opinion, both her genius and her weakness. For on first reading I defy anyone, however erudite and perspicacious, to catch her cryptic meaning at the speed with which we now expect to devour literature. It is a slow and laboursome journey of reading and sometimes re-reading which most I suspect, quite understandably, are simply not prepared to embark on. It demands not just your attention, but your life experience of that-which-is-left-unsaid, to absorb the abundant sustenance available in the dialogue. But if you do stay with her through the Latin and the French and the Gaelic and the cryptic allusions so historically accurate for the age, then the rewards are legion, as her fans will tell you.

It is not as though I think her without fault. There are times when my mental blue pencil appears in my hand and strikes through the excessive script which leaks tension like a sponge. Or I frown at the occasional clumsy plot construction, or the superhuman qualities and contradictions of her impossibly youthful hero, Lymond. But these are minor things compared to the breathtaking impact of the first introduction to Lymond’s cruel streak, in the incident of the burning helmet; or the description of the glittering French Court hunting; or the exquisite, restrained finesse with which she writes about that most difficult of subjects – sex. Dorothy Dunnett is unequivocally a writer’s masterclass.

So here I am, with pretensions to call myself a writer. My first novel is now completed and mentally laid aside and I am contemplating my next one. What shall I take from this Mistress of the historical adventure/thriller, the genre in which I seek to play? Not anything literal, that is for sure. You do not ape a Dorothy Dunnett and expect anything but derision; your own being first in line. No, I have taken two things: less is undeniably more and also, to understand what it is that you are good at and to excel in it. Then, your inescapable shortcomings will be readily forgiven.

Dorothy Dunnett, The Lymond Chronicles. There are 6 books in the series.

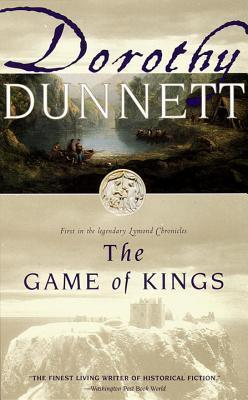

Book 1, The Game of Kings

Cover image courtesy of Amazon.

I’m reading this series for the fifth or sixth time, and I still feel like an archaeologist, uncovering layers of the story brush stroke by brush stroke.

Yes, I know what you mean, even though I’ve only read them twice I can imagine a third outing would give more insight. As a writer myself, there is always a question in my mind about how much I need to explain, and how much can be left to the reader to divine. When a character does something small, like finger her dress, there is an ocean of nuance going on in my mind. The reader can skip over it with a cursory acknowledgement of its significance or pause and delve deeper. With Dorothy Dunnett, the opportunities for delving deeper are legion, for she does not feel any compunction to explain, just to show. And she doesn’t give you all the subtle signals that help you understand, often it’s just the dialogue. Because she created those characters herself, she knows them before she writes about them, but the reader has to try and catch up and establish depth from the fragments she gives you. The first time through, that was hard, almost too hard in places. But the richness of the plot and setting carry you through. The only time you get direct insight into what Lymond is thinking and feeling is briefly when he tries to reach the ship, in The Ringed Castle and right at the end as he approaches Flaw Valleys. But she is a master writer and so, as a reader, you know that she knows, as she writes, what’s going on in his head, and so the incentive to uncover more is always there. I seem to have written an essay, not a response! Thanks for reading my post and I really hope you enjoy them again.